Date:11/26/24

Happy Tuesday, everyone! Today's fish of the day is the giant tube worm! Some of you may remember that this is an email from earlier this year, but due to some important exams, I figure a repeat of such an interesting animal can't be too bad.

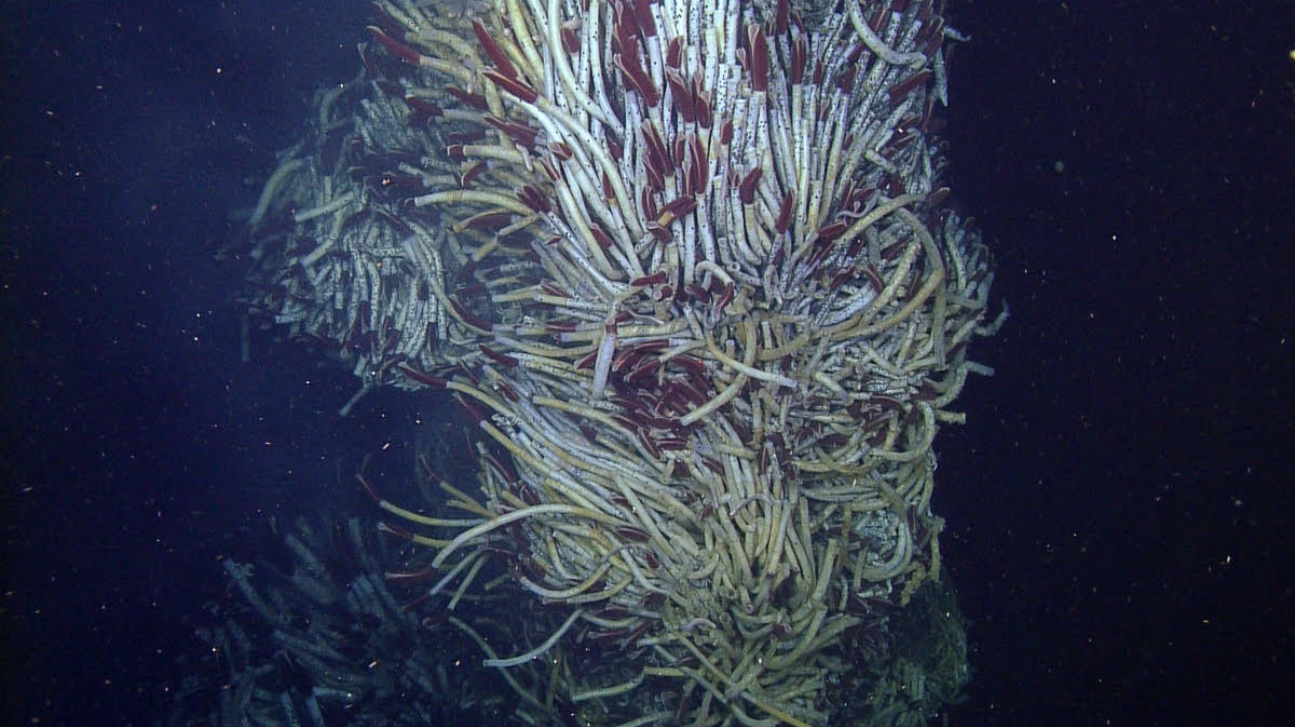

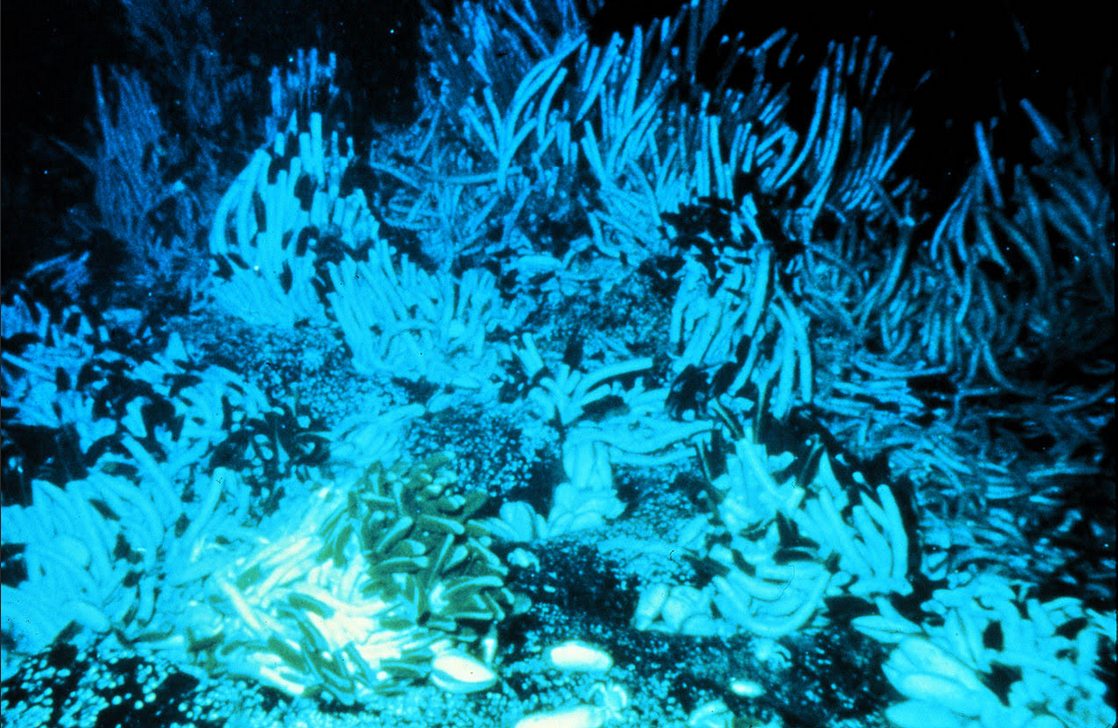

The giant tube worm, known by scientific name Riftia pachyptila is a common marine invertebrate. Unlike the common ship parasite of the same name, this animal is found in the deep sea, only discovered in 1977 when exploring the hydrothermal vents off the Galapagos islands in the rift nearby. The range of the tube worm is concentrated at rifts and trenches formed by tectonic plates around the world, and although they are theorized to possibly be in other areas of the world, they have only been recorded in the Pacific and Indo-Pacific oceans. Living anywhere from 2,564 - 2,673 Meters of depth (8,412- 8,770 feet) these animals have a life that is irreparable tied to the hydrothermal vents they concentrate around.

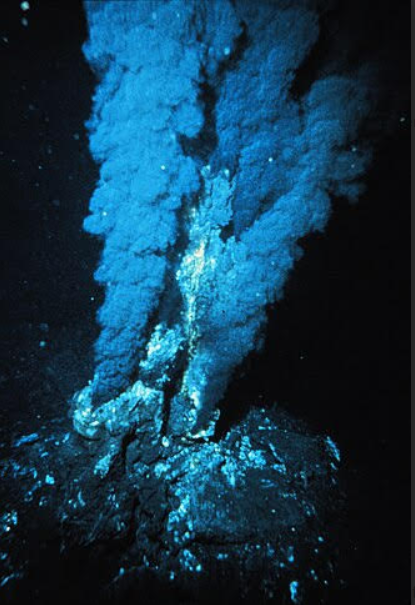

Due to their scarcity, hydrothermal vents are often misunderstood. These are fissure vents along the sea bed near volcanic activity that emits extremely heated water and chemicals. This supports environments of bacteria and archaea in the deep sea that previously could not have managed in the cold waters, with the trade off that the waters near them are anywhere from 60-440 degrees celcius (140-870 degrees fahrenheit). This works particularly well for the tube worms, as they prefer to live in warmer temperatures. In fact, when there were live specimens caught in 1998, the captive worms were found to enjoy living in environments around 80 degrees fahrenheit. These hydrothermal vents also foster the bacteria that keep adult worms alive, the Campylobacterota phylum.

The giant tube worm has a life cycle similar to many others within its family, worms start life as free swimming planktonic organisms, which swim weakly and move via rows of cilia along the outer layer of their skin. Once they find a hydrothermal vent, this is when they enter a sessile stage as a juvenile, where they will begin acquiring the bacteria around the vent within themselves. These worms have no mouth, and the bacteria is an essential part of the organism, acting as their only source of sustenance in a kind of symbiosis referred to as chemoautotrophic symbiosis. Once they are stably rooted into a colony around a vent, these worms will grow quicker than any other deep sea animal, breaking the ideas in 1977 about how slow life in the deep sea was. They can grow around 1.5 meters within less than 2 years, reaching a total or 2 meters or 6.6ft total, giving them the fastest growing rate of any marine invertebrate known.

The campylobacterota takes root in the tube worms similar to an infection, through the skin. This bacteria will then bloom inside of its host, starting at what was once the mouth and esophagus in juvenile and larvae worms, before taking place in the midgut. This bacteria will then carve out an area within the worm called the Trophosome cavity, and the remainder of the digestive tract fills in. This bacteria subsists off of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, from which it can create all organic compounds needed to sustain life, releasing sulfur as a waste product. It gains energy by oxidizing the inorganic sulfur in a cycle similar to the calvin cycle used for photosynthesis.

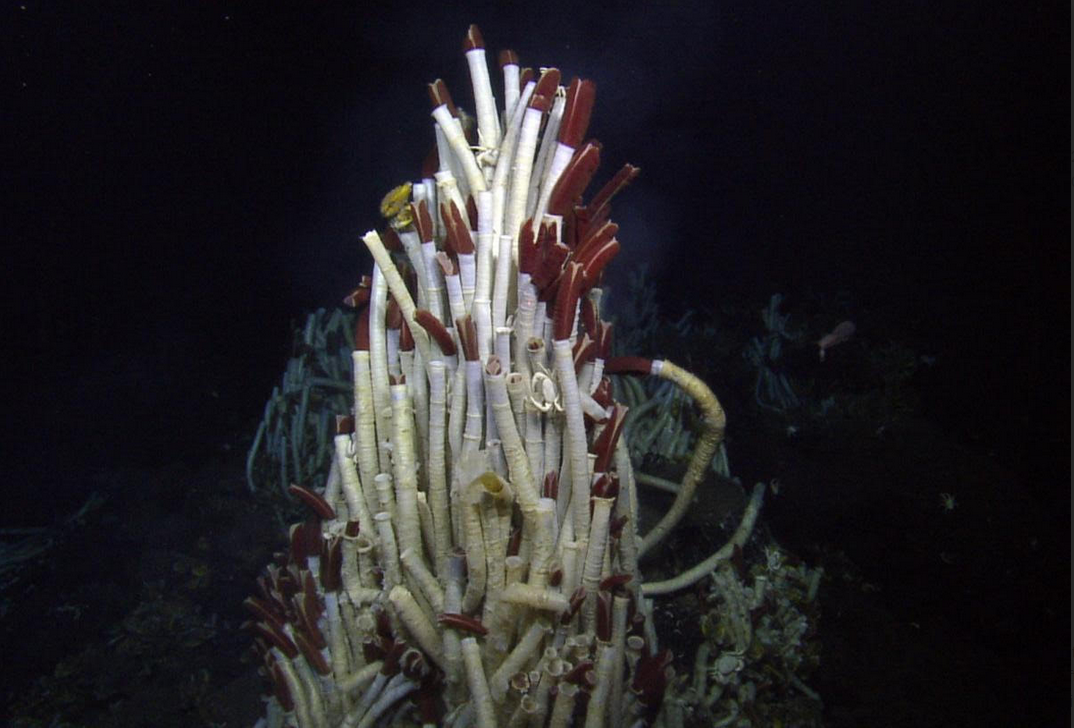

After the worm has settled into its home along the vent and has entered the symbiotic cycle with bacteria, the worm will begin growing what is referred to as a husk or a shalth around it. This is a hard chitin shell that is used to prevent predation on the internals of the worm, along with protection for the trophosome cavity within. Then, above that is the vestimentum, which are muscle bands that can be used to pull in a gill structure above in the presence of predators, this is also where the genitals can be found, and the heart. The most striking and visible section of the worm is the branchial plume. This plume is a bright red color due to the extensive hemoglobin chains within it, despite the presence of sulfides, which usually inhibit hemoglobins. These plume gill structures are used for extending into colder water where more oxygen is available, along with bringing in carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfides for the bacteria.

Reproduction of this animal is not reliant on a season or specific age, but rather to the volcanic tectonic plate activity around it. During a spawning event, males within the colony will release spermatozoa into the water, which will locate female tube worms, swimming within the husk structure and into the ovaries. In laboratory specimens, this process takes only 30 seconds, but in the wild it is thought to take much longer and survival of the spermatozoa to rely upon the hydrothermal vent. Once fertilized, eggs will grow within the worm for several months, and when the hydrothermal vent conditions are right, the eggs will be released into the water column, relying on deep sea currents and buoyancy to carry them to the pelagic layer. The life cycle begins all over again.

That's the giant tube worm! Have a wonderful Tuesday, and a great Thanksgiving break! Unlike earlier years, I will be continuing fish of the day throughout the normal break, so expect a new fish tomorrow!